We live in a richly textured, three-dimensional world, yet most technology flattens our experiences into pixels and panes of glass, reducing our interactions to clicks, scrolls, and taps.

From consumer wearables to workplace tools, augmented reality (AR) can untether us from our flat, two-dimensional screens. It has the power to bring us back to the physical world through technology designed around how we naturally move, think, and connect.

We believe that the future of AR is human-centered. Everything we design follows our core design philosophy that is tailored to enhancing human abilities.

Input with intent

The most effective AR interfaces are context-aware — they understand and recognize the contextual needs of the user and offer seamless interactions that feel second nature.

Designing with intention means thinking beyond traditional interfaces and towards intuitiveness. Adaptive input needs to align with both the task and the user, because people don’t interact with AR the same way in every situation.

For example, a surgeon with tools in hand or runner in the middle of their route might depend on voice commands. Meanwhile, a sound engineer on a hushed set or parent of a sleeping child may need hand gestures or eye tracking to maintain silence.

Support ergonomics and comfort

AR should feel like an extension of the body. People may wear AR wearables for hours at a time, so comfort isn’t optional, it’s essential and non-negotiable.

This begins with physical comfort. The device should rest on the face without undue pressure on the temples, nose, or forehead. Additionally, we must consider the device’s overall weight, how the weight is distributed, and the amount of heat produced by its components.

Comfort also applies to how we see through the device. Visual elements should feel easy to focus on and natural so we avoid nausea, eye strain, and fatigue.

We’ve found that when comfort becomes the foundation, performance and usability improve.

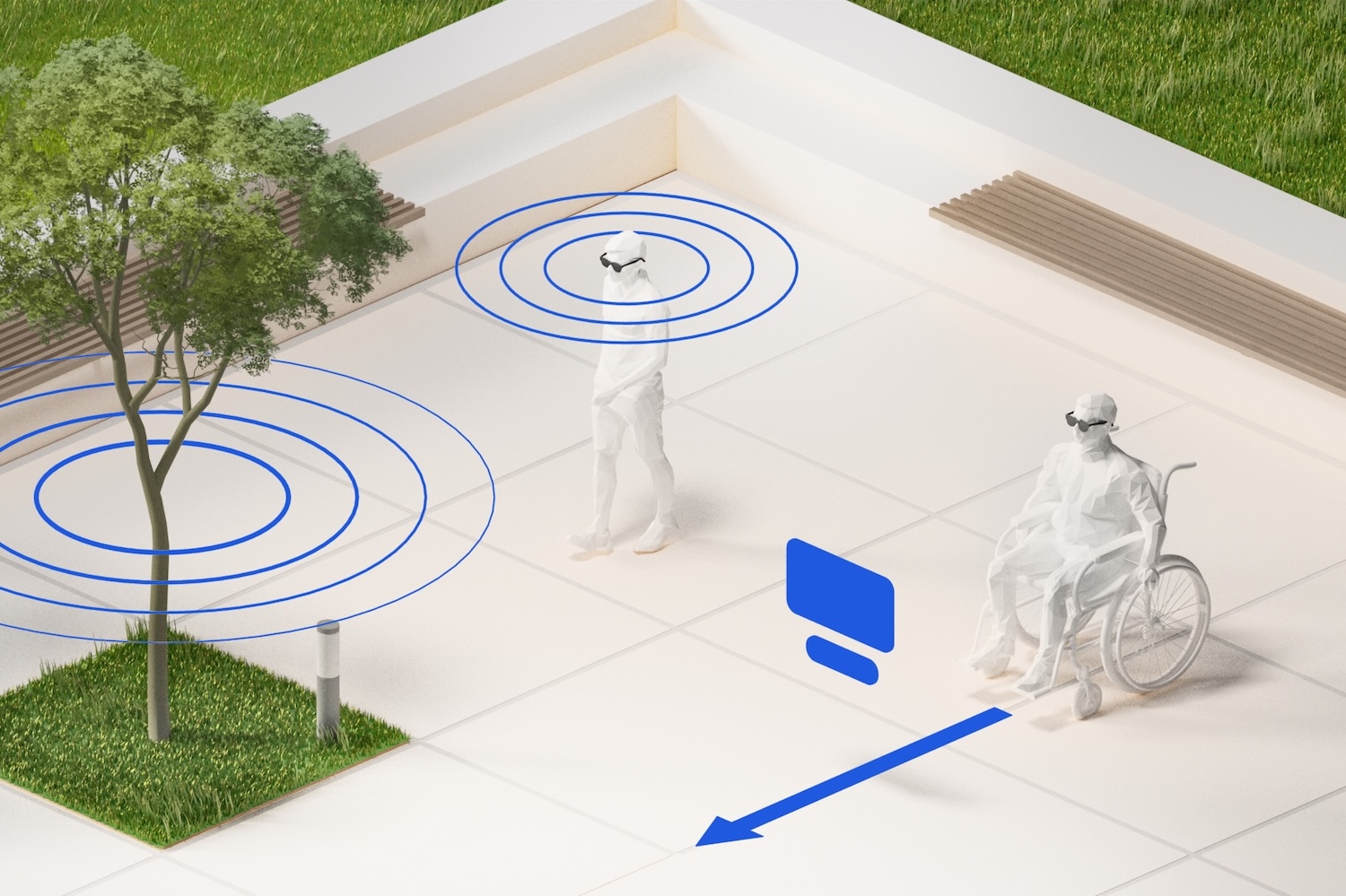

Include everyone

No two people are the same — differences in posture, mobility, eyesight, and familiarity with technology should also shape AR design. AR is uniquely positioned to make our world a more navigable and accessible place for all.

A few examples of inclusive design:

- Haptic pulses and real-time audio cues to support users with low vision

- Captions and text overlays to assist those who are deaf or hard of hearing

- Head gestures and eye tracking to replace touch or taps for users with limited mobility

When technology meets a wider range of human needs, it evolves from novel to necessary.

Anticipate intent

The most transformative tech experiences are perceptive and not just reactive.

Using contextual data and artificial intelligence (AI), AR systems can anticipate user needs like a helpful assistant who offers timely suggestions. It can surface reminders and instructions based on the environment and task.

For example, imagine you are training for a marathon. When you leave home for your run, your device could intuitively display a map with the most pedestrian-friendly route with needed mileage for your training that day.

With the right design, AR can heighten awareness, lighten mental load, and streamline or simplify everyday tasks.

Consider social dynamics

To be truly immersive, AR must blend seamlessly into the fabric of daily life. When designing for AR, it’s crucial to understand that while a library is no place for user voice commands, a busy factory may demand them.

Social dynamics not only apply to the countless inputs within the AR experience, they also apply to the hardware itself. What might feel natural or socially acceptable in one setting may feel completely out of place in another. For example, larger headwear may be appropriate on a factory floor, but is jarring and awkward at a nice dinner with friends. In all cases, the wearable device should match the situation.

Designing for the human first

AR has the potential to enhance how we work, learn, and live. But that future depends on designing for real human needs and dynamic situations. If we want AR to be more than a novelty, we need to design it for the people who’ll actually wear it, work with it, and rely on it. That means designing not just for tasks, but for bodies, minds, and moments. In doing so, we don’t just augment reality, we elevate it.